From the Dramaturg’s Desk: A Deep Dive into SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE

Director’s Note by Ethan Heard

“Anything you do, let it come from you, then it will be new. Give us more to see.”

I treasure this lyric as a mantra. In a season about artists making art, Sunday in the Park with George stands as the definitive piece of music theater on the topic. Personally, it’s my favorite show.

I first directed Sunday in 2012 as my MFA thesis at Yale School of Drama. Preparing this new production for Glimmerglass, I revisited my old notes — and the memories they carry. At the time, we reached out to Stephen Sondheim about the possibility of using a smaller orchestration. To our delight and surprise, he recommended that our music director, Dan Schlosberg (then a composition student), create a new arrangement: “Michael Starobin [the original orchestrator of Sunday and Assassins among many others] will happily advise you.” And Michael did, with extraordinary generosity. I remember visiting his home and listening as he and Dan discussed “the clarinet in bar 82” and how to bring out a motif more clearly. We soaked in every word. That collaboration planted seeds for future work. When I co-founded Heartbeat Opera in New York with my friend Louisa Proske (director of this season’s Tosca), Dan joined us as Co-Music Director and resident arranger.

In graduate school, I was approximately Seurat’s age when he painted A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. A central question in the musical struck me to the core: How do you balance art-making with life-building? Seurat in Act One and George in Act Two represent opposite ends of a spectrum. Lapine and Sondheim’s Seurat is a “genius”: visionary, obsessed, solitary, indifferent to financial success, and willing to sacrifice everything to “finish the hat.” George, the great-grandson they invented for him, is a showman: splashy, commercially successful, but disconnected from his inspiration. Leaving school, I hoped to land somewhere in between — and with a romantic partner.

Thirteen years later, I’m a busy artist still grappling with this question — still navigating the tension between joyfully “mapping out a sky” and worriedly “putting it together.” But now, I’m also a husband, and — just recently — a father.

Returning to Sunday as a parent, I find Marie’s wisdom more potent than ever: “There are only two worthwhile things to leave behind when you depart this world: children and art.” I also feel the story’s tragedy more acutely. Seurat dies at 31 — uncelebrated, unpartnered, and unable to greet or even acknowledge his daughter. (What motivates that choice — pride, fear, guilt?) As Dot and his daughter depart forever, he pleads with himself: “Connect, George, connect.” A century later, his great-grandson echoes those exact words. Fortunately for him, Marie’s red book, and the notes scribbled in the back, help him connect the dots…

In America today, artists and arts organizations are in crisis. As costs soar and government funding dwindles, some performing arts companies are fading away and many artists are choosing other paths. Now more than ever, we need to champion artists and to remember why art matters. We gather in community to feel something together, to harmonize together, to cherish what connects us.

The whole team and I invite you to enter the world of our hat. May it delight you. May it move you. And may it remind you — like it reminds me — of the beauty and necessity in trying to connect.

Sondheim’s Secret by Michael Ellis Ingram

“Good artists borrow, great artists steal.” A version of this aphorism has been credited to innovators from Pablo Picasso to T.S. Eliot, Igor Stravinsky to Steve Jobs. The influence of one creator on another shows up in many forms: Artists may sample, elaborate on, or react against the work of their peers and predecessors. Georges Seurat’s vision, while undeniably unique, developed in conversation with the visions of so many others — painters of his time, anonymous sculptors of antiquity, scientists concerned with color theory and vision. Likewise, Sondheim’s singular musical drew on a wide range of influences, explored here by Michael Ellis Ingram, who conducts the Glimmerglass production.

Make sure no one is looking over your shoulder when you read this. I’m about to tell you a secret…

Stephen Sondheim drew from a dozen different 20th-century styles of classical music to create the inimitable sound world of Sunday in the Park with George. There are lush gardens of sound, as in the late chamber music of Gabriel Fauré and harmonies too achingly beautiful for words. There are dense thickets of rhythm in which every instrument plays a different motif simultaneously, as in that first great climax of The Rite of Spring. Sondheim translated Seurat’s obsessive pointillistic brushstrokes into the mesmerizing minimalistic grooves of John Adams and Philip Glass. (Incidentally, Steve Reich, that other pioneer of minimalism, shared a 40-year friendship of mutual admiration and inspiration with Sondheim.) There is the kind of yearning, distinctly American dissonance you hear in Copland and Bernstein; it makes you feel homesick wherever you are. There are unexpected, heart-wrenching modulations found only in the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, which Sondheim called his “desert island” piece. (When you hear the duet “Move On” in Act Two of Sunday, think of “Oh Bess, Oh Where’s My Bess.”) There are subtly shifting planes of sound, sometimes perfumed like a Debussy prelude and sometimes inscrutable as a Schoenberg Klangfarbenmelodie. The vast world-building soundscapes of Holst and Sibelius, the controlled cacophony of Ives, the Parisian dance hall music sprinkled throughout Poulenc and Milhaud, Scriabin’s synesthesia-infused sound experiments, Puccini’s soaring lyricism — they all find their place in Sunday in the Park with George.

Speaking of Puccini — and please double-check that no one is eavesdropping — Sondheim didn’t like opera much. He found the acting static and complained that words in a foreign language stretched to the breaking point were not the best way to communicate with an audience. Nevertheless, voracious as he was in his stylistic appetite, Sondheim reached deep into the operatic tradition for inspiration while composing Sunday. He borrowed Rossini’s tongue-twisting patter for comedic effect and crafted multi-layered Mozartian ensemble scenes that dazzle the ear with their speed and contrapuntal virtuosity. He included cheeky little snatches of Viennese operetta reminiscent of Lehár’s The Merry Widow or Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus. His choruses conjure something sacred and anthem-like in the tradition of Verdi’s “Va, pensiero.” He put together a network of leitmotifs to rival Wagner’s Ring Cycle, combining and transforming them with kaleidoscopic inventiveness.

A Chromolume for Glimmerglass by Michael Ellis Ingram

Sondheim and Lapine cleverly peeled the word “chromolume” from the obscure term “chromoluminarism,” which is what Georges Seurat preferred to call his painting technique. Sondheim and his young orchestrator Michael Starobin provided copious music for the chromolume sequence in Act II, but they also allowed each production of Sunday to adapt the music to the individual set design. It is a delicious challenge to craft new music for this scene, not to mention humbling to presume to add something to this stunning score. The chromolume needs to be spectacular and odd and a bit too much. It should leave the audience wide-eyed with wonder…but also with a question mark in their thought bubble. Ethan suggested that we incorporate a sound that doesn’t show up anywhere else in the score: a cappella voices. I used my little cottage in Cooperstown as an improvised recording studio to create demos of what the chromolume might sound like. I layered my own voice dozens of times singing color names and short rhythmic phrases like “color and light.” I also sang a few melodic fragments from Act I to create a driving minimalistic sound collage. It was such great fun to re-record these strange little “color swashes” with four of our incredible Resident Artists (there was no sheet music, mind you) and then to let Joel Morain add his stereophonic sound designing magic to the sequence. We hope you are dazzled — and ever so slightly perplexed — by what we came up with.

The voices of the Glimmerglass Chromolume are Claire McCahan, Reed Gnepper, Erik Nordstrom, and Angela Yam.

Getting to the Point by Nick Richardson

“The Neo-Impressionist does not dot, he divides.”

(Paul Signac, artist and follower of Georges Seurat, 1899)

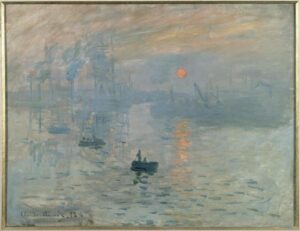

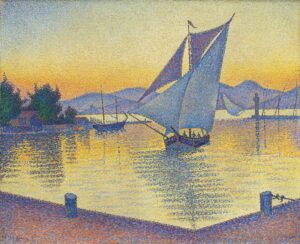

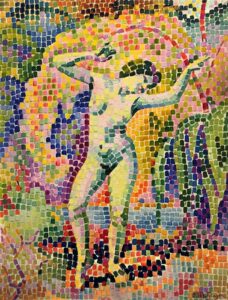

Seurat pioneered Chromoluminarism, a method in which the artist applies individual dots of a singular pigment to the canvas – without mixing pigments together on the palette to create other colors. The juxtaposition of colors next to each other allows the viewer’s eye to blend colors together, which creates brighter, more luminous hues than pigments mixed beforehand. This use of color marks a stark contrast to the darker, muddier shades often found in academic painting.

Seurat’s technique falls under the broader term Divisionism. Colors are divided into sections on the canvas, but the brush strokes don’t have to be dots; they can take different shapes, like thick rectangles from a brush head or even thin strips of paint. Using dots to compose an image is called Pointillism, after the French word pointe, meaning “point” or “tip.” The difference here is that Pointillism doesn’t necessarily suggest separation of colors; in fact, some pointillist works are entirely one hue. Pointillism was originally coined as an insult against Seurat, yet it remains common terminology today.

|

|

Compare the thick square brush strokes of La danse, Bacchante by Jean Metzinger (1906), a Divisionist work, to the fine Pointillism of Theo Van Rysselberghe’s Portrait of Irma Sèthe (1894).

Everybody Loves La Grande Jatte by Nick Richardson

Now considered a familiar masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte was initially panned by many of Seurat’s contemporaries for its technical, machine-like dots of color and casual subject matter. At the eighth (and last) Impressionist Exhibition, it was kept in a separate room along with other Divisionist works. The piece lay dormant for nearly three decades after Seurat’s death until esteemed American art collector Frederic Clay Bartlett purchased the piece in 1924 and loaned it to the Art Institute of Chicago, where it remains today. It is now a calling card for the Institute and a cultural icon in itself.

La Grande Jatte received prominent attention in the John Hughes film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. When Ferris skips school with his girlfriend Sloane and best friend Cameron, one of their many excursions is the Art Institute of Chicago. Cameron is transfixed by the painting, and in a series of increasing close-up shots, we see Cameron juxtaposed with the little girl in Seurat’s piece. Hughes says, “The closer he looks at the child, the less he sees, of course, with this style of painting. The more he looks at it, there’s nothing there. He fears that the more you look at him, there isn’t anything to see. There’s nothing there. That’s him.” It’s a pivotal turning point in the movie, as Eleanor Harvey, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, explains: “Cameron could not have anticipated that this would be anything but a fun goofball day and in a sense that painting becomes our first concrete clue that Cameron is deeper than everyone else in that movie.”

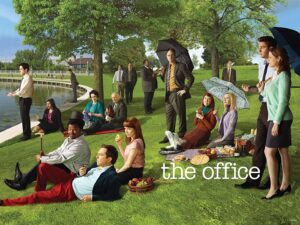

On the small screen, Family Guy parodied La Grande Jatte and even Seurat himself. Stewie also had his own Day Off moment when seeing the painting in person. The Simpsons also referenced La Grande Jatte in multiple episodes. Though the painting wasn’t featured in NBC’s hit series The Office, the cast did recreate the painting as a promotional photo.

|

|

|

Speaking of promotion, clothing company Lands’ End used the painting in its advertising campaign 100 years after Seurat finished his masterpiece, updating the familiar scene to the 1980s.

Even The Muppets found their way to the island of La Grande Jatte. The illustration below was included in a Sesame Street alphabet book from 1989.

Today, you can carry La Grande Jatte wherever you go – without the hassle of a giant canvas or frame – thanks to Discover Card. The original painting is about 7 feet by 10 feet, but this version measures just 2 by 3 inches.

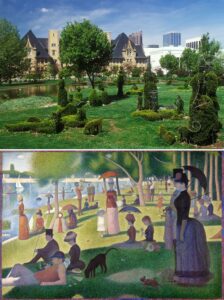

Ready for your own scene in the park? Topiary Park in Columbus, Ohio is a recreation of Seurat’s painting made entirely out of plants. It’s the only park in the world based on a painting. The city chose La Grande Jatte because “all of the figures are sort of individual, which means that they would be easy to represent in a garden by putting a single plant to represent each character.” Another option is Lindsay Park in Davenport, Iowa, where fiberglass recreations of Seurat’s characters pose along the Mississippi River.

The Art of Funding Art by Olivia Gacka

For as long as there have been artists, there have been arts patrons. As we see in Sunday in the Park with George, the act of creation is inextricable from the ability to pay for it, or to make it pay. Art is one of the many human outputs to which we (perhaps strategically, perhaps arbitrarily) attach a monetary value on the basis of its subjective rather than objective worth. As a result, the creation of art across mediums is often pursued without the guarantee of a financial return. Although the first major example that often comes to mind is the Renaissance model, there are records of arts patronage stretching back centuries, well into ancient times.

The role of the patron within the creative process has varied throughout history depending on the patron’s motives. In some instances, the patron had direct influence over the artistic output. In others, the patron would give directives, but the artist would either subversively or explicitly go in another direction. Some arts patrons aimed to buy their immortality through patronizing an artist, or to promote their own ideals. Some wanted to support particular artistic movements, or were simply fascinated by the creativity of art and artists. Regardless of their aim, an arts patron is someone who, through their support, communicates their belief in the power of art.

For centuries, artists almost exclusively came by institutional or large-scale individual support from monarchs or the elite. This concentrated the power to support art to the wealthy and powerful. Today, individuals of all means have the opportunity to be an arts patron via individual gifts to institutions or by supporting artists directly. But patronage isn’t strictly financial; it often includes gifts of time and talent through volunteering efforts. While we do still see instances of large-scale individual and institutional support, the legacy of arts patronage is clearly visible in these other iterations. This grassroots support can also be found in the origins of organizations like The Glimmerglass Festival itself, organizations founded on the understanding that the arts is a point of civic pride, that the collective support of such endeavors enriches the whole. Arts patrons throughout history, though different in their approach, are united in a belief that art does not always produce fiscal wealth, but can produce cultural, intangible wealth.

That is not to say that the arts do not present opportunities for financial benefit to the whole: According to research compiled jointly by the National Endowment for the Arts’ Office of Research & Analysis and the Bureau of Economic Analysis out of the U.S. Commerce Department, no state in our nation saw less than a 1.4 billion dollar value added by the arts to their economy in the year 2023 alone. The task of facilitating the art which contributes to our global cultural life has never been solely in the hands of the artist, and arts patrons in all shapes and forms should see themselves as a key factor in the artmaking process.

Artistic output is a cycle, in which patrons of all kinds play a crucial role. The patron commissions, the patron supports, the patron consumes. In every area where the artist is a necessity, there we may also find examples of patronage. For whom do we paint? Perform? Produce? Regardless of the ways or means by which the patronage is expressed, the presence of patrons has always been a key factor in “the state of the art.”

MORE TO EXPLORE

Give us more to hear: Conductor Michael Ellis Ingram’s playlist offers an aural accompaniment to his essay on Sondheim’s influences for Sunday in the Park with George.

Color and light… and lasers? In this blog post from the New York Public Library, see how different designers have interpreted young George’s Chromolume in both high-tech and low-tech, even human, ways.

Collaborating on Sunday was no walk in the park; in fact, Lapine called it a “complicated and occasionally painful” process. Hear from Lapine, Sondheim, Bernadette Peters, and many other artists in Lapine’s oral history, Putting it Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created Sunday in the Park with George, reviewed here in American Theatre magazine.

Sondheim as Rabbi: Gabrielle Hoyt explores what makes Sondheim’s musicals Jewish in her article for American Theatre magazine.

En pointe-illism: Director/choreographer Eamon Foley always envisioned setting the music of Sunday to contemporary ballet. Check out his music videos for “Color + Light” and “Finishing the Hat” featuring pointe dancers.

Is George Seurat a likeable character? Producer Katie Birenboim teams up with actress Talia Suskauer and director/choreographer Eamon Foley to discuss Sunday’s “essential problem” on her podcast, Call Time. (You can preview their conversation in this blog post on ArtsJournal.)

“In creating a work about a pioneer of modernist art, Mr. Lapine and Mr. Sondheim have made a contemplative modernist musical that, true to form, is as much about itself and its creators as it is about the universe beyond,” wrote Frank Rich in his review of the original 1984 Broadway production for the New York Times. Read the whole thing here.

With 100 years separating George Seurat from his great-grandson, Sunday presents two very different pictures of how to navigate the art world socially and commercially. Compare “The Role of the Artist” in this piece from Music Theatre International.