From the Dramaturg’s Desk: A Deep Dive into THE HOUSE ON MANGO STREET

A Note from the Author by Sandra Cisneros

I began The House on Mango Street from a place of anger. I was at the University of Iowa at the famous Writers’ Workshop, and I felt like anytime I spoke, people looked at me like I came from Mars. One day in the seminar, we were talking about our houses, and it occurred to me that I had never seen my house written about in a library book or in a movie or in a newspaper. I had never seen my house or my community written about with love. And it was quite shocking for me. My first thought was, I don’t know if I belong in this Writers’ Workshop. I don’t know if I should stay in this program. Maybe I should quit. But the wonderful thing about depression — on the other side of it is rage. After you’ve gotten through being depressed, there’s a little bit of anger. Why haven’t I seen my home written about with love? I’m not going to quit. I’m going to write that book.

After I left Iowa, I went immediately into one of the poorest neighborhoods in Chicago, an immigrant community. I was supposed to be the teacher, but I was learning from the lives of my students. Their lives humbled me and transformed my anger. I started using the stories from my students and weaving them into a neighborhood, and that neighborhood became Mango Street.

I think when we feel most powerless, or we feel like we’re empty and have nothing to give, that puts us in a state of grace. I think many teachers share this feeling. You feel like you can’t save your students and there’s nothing you can do except listen to their stories and teach them love.

I had these stories in my heart, and I put them down on paper so that I could let them go. I had no intention of getting any fame or winning any awards. It taught me a life lesson: Whatever we create with love will turn out well — siempre sale bonito.

So that’s how the book was born. The story is still growing and surprising me all these years later. I wish the problems brought up in the book had been solved so we wouldn’t have to keep telling these stories 40 years later. The timing of this opera could not be more perfect, because it is the story about an immigrant community, about poor people, about Latinos, about so many people who are being vilified right now.

I hope this opera will bring a younger, fresher, newer audience to the opera. I grew up with opera. I didn’t know you had to pay to listen to it. I heard it in the park for free. My mom borrowed opera records from the Chicago Public Library, and she sang arias in the kitchen when she was cooking. We always had opera music going in the background.

I had never done anything like this before, but I realized that a librettist is just a poet. And writing a libretto is easier than writing poetry when you have someone like Derek. I could write a whole page of poetry, and he would take the best lines and throw out the rest. And that was fine with me. Writing by yourself is really hard. It is so much more fun to do with your friend.

One of the things I’ve learned is that making opera is like getting a big jet off the ground. You have a pilot, and you have mechanics, and you have stewards, and you have someone at the control tower. And so you are not working on it by yourself. You have this whole team that has to work together to lift off. And that requires a lot of sharing and trust and gratitude.

Composer’s Note by Derek Bermel

I first read The House on Mango Street in 1991 at the advice of one of my dear friends, Wendy S. Walters, who had been a student of Sandra’s at the University of Michigan. What I love about Sandra’s writing, and what stays with me, is that it is simultaneously whimsical, outrageous, tragic, and touching — a mix of emotions that’s profound and multi-layered. Yet there’s a simplicity and directness in the language; The House of Mango Street sang to me, straight off the page. Sandra was gracious enough to grant me the rights to set several of her songs, and when she and I met for lunch after that, I popped the question: I asked, will you write an opera with me? And she said YES!

Part of the fun — and challenge — of telling a story with so many vivid characters is discovering the musical voice that can bring each of them to life. Esperanza’s music is full of longing and melancholy, communicated in her diary as she relates anecdotes from the neighborhood. Her voice is lyrical, but exudes a sense of dissatisfaction, restlessness, and passion; I think those qualities manifest in the jazz harmony of her arias. She’s also a poet, a dreamer, so sometimes her musical language goes to a very abstract, floaty place. We’re catching her at an interesting moment in life, when she’s just discovering her own powers.

Then you have characters like Lucy and Rachel, who are from the Texas/Mexico border. Around the 1830s and 40s a bunch of Czech, Polish, and German immigrants settled in Mexico carrying their accordions, which combined with the Mexican indigenous music, becoming what is now referred to as Tejano/Norteño, or Conjunto, style. These songs are straightforward harmonically but deceptive rhythmically, with elisions similar to what you find in odd phrase structures of Mozart — an extra beat here, an extra bar there. And there’s Sally, who busts out in a gospel-tinged ballad, Sire and Tito who tell their tales through rhyming hip-hop narration, the vendor Geraldo who sings a wistful ranchero, the anxious Alicia, who offers up a pop-infused anthem. And of course, there is music that reflects influences from the long history of opera.

As we worked on the opera, Sandra and I tried to focus on moments in the book that we felt spoke with urgency for this moment. Sandra told me that her mom used to say, ‘Just enough, not too much.’ And I feel that The House on Mango Street strives for that balance; it doesn’t push, but it gently allows us to see ourselves — and the hopes and dreams of others — in a new light.

— Derek Bermel

The House on North Campbell Avenue by Nick Richardson

If you try to find Esperanza’s house at 4006 Mango Street on a map, your search will come up empty. There is no Mango Street in Chicago. The house and neighborhood that inspired Sandra Cisneros’s novel is at 1525 North Campbell Avenue, just east of Humboldt Park, a predominantly Latino neighborhood with strong ties to Puerto Rico.

Cisneros’s family spent her early childhood between Chicago and Mexico City. They moved into the house on North Campbell Avenue when Sandra was 11, and she lived there through middle school and high school. That house was demolished in 2004, and on the property now sits a three-story brick condominium with bay windows and a wrought iron fence. To get a sense of Sandra’s house, look across the street at 1524. It’s “small and red,” with “windows so small you’d think they were holding their breath,” as Esperanza describes.

After finishing high school, Cisneros stayed in Chicago to attend Loyola University for a degree in English. She then moved to Iowa for her MFA, and later to San Antonio, Texas to write and teach. She now lives in Mexico, though as she told Univision, “I found my voice and my home in writing. And I can take my writing to any country.”

Esperanza’s Barrio: Humboldt Park by Nick Richardson

Whose neighborhood is it, anyway? As Esperanza tells us in the novel, families like her white friend Cathy’s will “just have to move a little farther north from Mango Street, a little farther away every time people like us keep moving in.” Sandra Cisneros was 11 years old when she moved with her family to Humboldt Park, a neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side. In its 150-year history, Humboldt Park and its community have seen waves of immigrants from Europe and the Americas, lived through the mid-20th century “white flight” to the suburbs, and actively resisted the gentrification of this millennium.

Between 1869 (when the Park was first annexed into the city) and 1900, Danes and Norwegians settled in the area northwest of the Park. Polish populations soon joined the area, followed by Italian Americans and German and Russian Jews in the 1920s and 30s. By the 1960s, most Jews had left for neighborhoods north of Humboldt.

The first wave of Puerto Rican immigrants to Chicago came in the 1940s to work in the steel industry. Failed urban planning forced Puerto Ricans to move to Humboldt Park in the 1960s. In 1966, a three-day riot ensued (the Division Street Rebellion) after police shot and wounded a young Puerto Rican man, an event emblematic of the rising ethnic tensions within the community. Through the rest of the 20th century, Mexicans and Dominicans joined Puerto Ricans in the barrio. Today, Hispanics and Latinos of any race make up nearly 50% of the neighborhood’s population, followed by Black Americans at 35%.

Humboldt Park itself illustrates this wide variety of ethnic and national origins. In the Park, you can find statues of German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (for whom the Park is named), Norse explorer Leif Erikson, and Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a Polish exile who served in the American Revolutionary War. Noticeably absent among these statues is Don Pedro Albizu Campos, a leader in the movement for Puerto Rican independence from the United States. His inclusion in the Park was deemed too controversial; instead, his statue is located nearby on Division Street.

Nevertheless, Humboldt Park remains the epicenter of Puerto Rican Chicago. The Park is home to the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture. Southeast of the park is the Paseo Boricua, the “Puerto Rican Promenade,” which is flanked by giant steel Puerto Rican flags. Paseo Boricua was named an honorary municipality of Puerto Rico (the 79th of the island nation’s 78 municipalities) and flies the country’s official Municipal Flag.

Tu propio paseo: Take a free audio tour of Humboldt Park, the 207-acre green space designed to bring the prairie countryside to the city, said its architect Jens Jensen.

“I have lived in the barrio, but I discovered later on in looking at works by my contemporaries that they write about the barrio as a colorful, Sesame Street-like, funky neighborhood. To me, the barrio was a repressive community. I found it frightening and very terrifying for a woman. The future for women in the barrio is not a wonderful one. You don’t wander around these ‘mean streets.’ You stay at home. If you have to get somewhere, you take your life into your hands. So I wanted to counter those colorful viewpoints, which I’m sure are true to an extent but were not true for me.” 一Sandra Cisneros

The Material You Are About to See is Banned (Somewhere) by Olivia Gacka

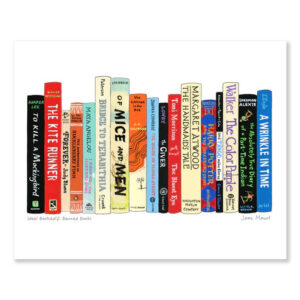

The history of book banning in the United States is a long one, predating the forming of the nation itself. Book bans remain prevalent today, with over 10,000 books banned in schools in

the 2023-2024 academic year. The list of books that have faced bans throughout our history include many now considered indisputably canonical works of American literature, including Huckleberry Finn (Twain), To Kill a Mockingbird (Lee), I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings (Angelou), Leaves of Grass (Whitman), The Catcher in the Rye (Salinger), and The Crucible (Miller). In many ways, using the books banned in the United States to assemble a reading list, one would find themself with a stack of some of the most renowned works of literature in the world. Award-winning American writer Sandra Cisneros set out to do a version of just that by challenging herself to read the 676 books banned in South Texas last year alone. Add to that list her own book, The House on Mango Street, whose operatic adaptation gets its world premiere here at the Glimmerglass Festival this summer.

While the opera itself is not censored in any way, its source material has been banned in school systems across the United States. The reasons for the bans vary, but most are concerned with the book’s representation of everything from sexuality to social issues, and even for its focus on Latino characters. Cisneros, who also serves as the librettist for our operatic adaptation, has spoken on the issue of censorship in literature. In her op-ed for the New York Times, she reiterated her position that banning books does more harm than good by preventing opportunities for understanding and learning.

In commissioning and programming The House on Mango Street, The Glimmerglass Festival is fulfilling several of the mandates set out in its mission statement: in particular, to produce new work and to inspire dialogue around meaningful issues of the day through song and story. But it also includes the company in the time-honored theatrical tradition of performing censored material!

In addition to literature, theater in schools is another medium with a track record of heavy censorship, to the chagrin of educators. According to the Educational Theater Association, 63% of theater educators surveyed cited the influence of censorship in their programming decisions, and 78% cited instances of pressure from administrators, parents, or community members to change their programming decisions due to content concerns. Of that last group, 22% of teachers were forced to make changes to their planned seasons on this basis. Like literature, theater provides mechanisms for students to build empathy, gain confidence, and discover personal and civic identity; so banning or censoring materials that reach the stage presents similar limitations.

So as you sit down to watch the world premiere of The House on Mango Street, take a moment to reflect on how lucky we are to make the decision for ourselves to experience this material, to explore worlds that are not our own, to hear voices that are new to us, and to take a walk on Mango Street.

MORE TO EXPLORE

This may be Cisneros’s first time writing a libretto, but it’s not her first time writing song lyrics. Listen to her song “Squink” from her latest book of poetry, Woman Without Shame, performed by her brother, Henry Cisneros.

“I’m learning more and more about the characters. They’re still talking to me after all that time,” says Cisneros. Hear her take on the novel today – and about the opera, too! – in this interview from last year’s National Book Festival at the Library of Congress.

Spirituality is part of Cisneros’s unending search for home. See how she reached her own form of Buddhism in this article from Lion’s Roar.

He grew up listening to jazz and hip hop while taking clarinet lessons. He traveled the world to explore music cultures and study with international composers. Now he’s a three-time Grammy nominee. Get a taste of composer Derek Bermel’s music (and see him rap!) in this video, then read his conversation with New Music USA about his vast musical influences.

Want to compose music for orchestra, but don’t know where to start? Take a lesson from Mango Street composer Derek Bermel. He teaches how to study orchestral scores in this webinar from the American Composers Orchestra.

Segregation in Chicago not only targeted Black Americans, but Latinos as well. Historian Mike Amezcua’s essay chronicles the fight for fair housing in Chicago’s Southwest Side and how Latino activism was distinct from the Civil Rights Movement. You can learn more in his book, Making Mexican Chicago.

Introduce your little ones to Mango Street with this bilingual picture book: Hairs / Pelitos is a story from the original novel with illustrations by Terry Ybáñez. Buy it here.The next generation: For your next read, check out these five Latina authors directly inspired by Sandra Cisneros and her House on Mango Street.