Spring has truly sprung! Fields of snow became fields of daffodils almost overnight, and the sun is gleaming off Otsego Lake reminding us exactly why James Fenimore Cooper was inspired to call it “Glimmerglass.”

On campus, apprentices and seasonal staff are starting to arrive, buildings are being dusted off, sets and costumes are appearing from our shops, and final pieces of casting fall into place. This is a time of expectation and excitement before the explosion of creativity the Festival brings to the area each summer.

As this anticipation vibrates through campus, I’d like to continue to offer you my insights into the many reasons to be excited about our upcoming 2023 Festival. This month, let’s take a closer look at the two early works in our season, Rinaldo and Love & War!

Countertenors

For Glimmerglass, spring also brings our annual gala at New York’s stunning Metropolitan Club. This year’s event was held on April 4 (click here to see some wonderful photos of the evening). Thank you to all of our guests and artists for making the evening such a success!

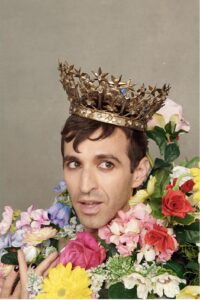

One star who couldn’t join us that night (citing some lame excuse about reprising his iconic interpretation of Akhnaten at English National Opera while presenting the Olivier Awards for Opera in his spare time) is our glamorous and brilliant Artist-in-Residence this season, Anthony Roth Costanzo. Anthony is one of the world’s reigning countertenors, and the star of our new production of Handel’s first box-office smash on the West End, Rinaldo.

We’re lucky enough to have two more wildly talented countertenors on stage during Rinaldo this season, benefiting from working alongside our acclaimed Artist-in-Residence. You’ll be amazed at these voices.

Cross-Dressing

Back in 1711, however, the role of Rinaldo’s pal, Goffredo, was sung by a woman – specifically a “contralto en travesti.” Then in Handel’s 1731 revision, Goffredo became a tenor, and the Sorcerer moved from castrato to bass. Throughout opera and theater, and very often in Baroque works, we have the choice of casting a role with a singer of any gender and a range of voice types. The characters they play can be monarchs, servants, gods, mythological beings, romantic leads, comic relief – well, anything really. The costumes they wear are as varied as the characters they represent, the words they sing, and the choices they make. While this isn’t the place to dive into the drag debate that has been raging across the country, it does at least seem to me that the current discussion should be about content and not costumes – cross-dressing, especially on stage, is a practice as old as we are and a vital form of self-expression.

Crusades

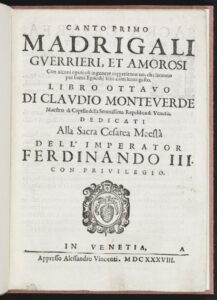

Rinaldo brings up another topic we need to address this season, a series of terrible religious conflicts between Christians and Muslims over possession of some of their most sacred sites: the Crusades. Rinaldo is set during the First Crusade of 1096, and although our fantastical production downplays the religious elements and reframes the action in a child’s imagination, the subject still warrants conversation. The pieces I’ve chosen to spark this discussion come from Monteverdi’s Eighth Book of Madrigals. We’re calling the project Love & War after the collection’s original title; the first of the two works is an 18-minute mini-opera that describes a day-long battle between two knights of the First Crusade, Tancredi and Clorinda.

Musically, this piece is unlike anything else. While we now take for granted that we can set speech to music and that music can describe dramatic action (in this case, a fight to the death), this wasn’t always the case. In the West, the concept was largely invented by a group of Italian composers during the Renaissance who wanted to recreate the ideals of Ancient Greek theater, which was entirely sung. The greatest of these composers was Claudio Monteverdi. We now call the ground-breaking system he developed stile rappresentivo (representative style), and specifically in this piece, stile concitato (agitated style). From these, composers like Handel developed the wordier recitative and the song-like aria, both of which we hear throughout Rinaldo.

Monteverdi’s miraculous original conception was never bettered. Every moment of the battle, every change of pace, thrust of sword and spear, gallop of hooves, or heavily armored footfall is captured by the narrator and the music. To achieve this, Monteverdi employed entirely new techniques, such as asking his string players to pluck their strings with two fingers or to play rapid repeated notes (the very first time pizzicato and tremulo were used in string writing). Most remarkably, he created a real drama: we feel immense pathos when Tancredi mortally wounds Clorinda, only to lift his opponent’s visor and discover he has killed his own lover. So full of movement and passion is the piece that it cries out for dance, which our director and choreographer Eric Sean Fogel will provide with the help of our talented Festival dancers.

And yet, this amazing piece is also problematic and worth discussion in a modern light, just like the beautiful painting above (which entirely whitewashes Clorinda). At the very end of the piece, the Muslim Clorinda asks to be baptized by the Christian Tancredi before she expires – but why? We’re treating this as a double betrayal (of their love and her faith) and will follow the tragic battle with the sublime Lament of the Nymph. This heartbreakingly beautiful song of a betrayed lover it is one of the most perfect pieces on a ground bass ever composed (Dido’s Lament, Pachelbel’s Canon, the last movement of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony, and U2’s “With or Without You” are other well-known examples of pieces based on a ground bass.)

Love & War plays August 3 + 17 in the Pavilion, and features this season’s Romeo, Almirena, Candide, and Friar Laurence:

Our Pavilion projects this summer are a perfect addition to your Festival experience – they will inform your understanding of the pieces you see on the Mainstage, get you closer to our leading artists, and allow you to enjoy great food and drink with other opera-lovers from around the world. There aren’t a lot of tickets to go around though, so book your tickets now to avoid disappointment!

Purchase Your Tickets Today to Love & War

Purchase Your Tickets Today to An Evening with Anthony Roth Costanzo

Header Image︱Otsego Lake︱Photo by Brent DeLanoy

Interesting question as to why she would ask for baptism, and certainly if you approach it from the perspective of Monteverdi’s era and its cultural biases, there are a number of logical answers. But you’re correct to try to inhabit the perspective of an upper-class Muslim woman of that period. She’s decided to be honest with herself in death because she knows she’s messed up on so many levels that she may as well abandon her spirituality, too. Indeed, the comparison with Dido is apt. But she outdoes Dido in that she commits a suicide of her soul and not just her body.